Human rights activist: Hamad bin Isa established a regime based on dictatorship and oppression

Prominent human rights activist Maryam Al-Khawaja said that Bahrain’s King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa established a regime founded on dictatorship and repression and crushed any peaceful opposition in the country.

In an interview with Democracy Now for the Arab World (DAWN), Al-Khawaja stated that the crackdown in Bahrain began in August 2010 when Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa said that he would introduce a constitutional monarchy.

“We didn’t know he thought what we currently have is a constitutional monarchy, and obviously it’s not,” she said. He unilaterally changed the constitution to make himself a king, make Bahrain a kingdom, and then set up a parliament with no legislative, accountability, or oversight powers. So, he created a system in which he became more of a dictator than his father.”

Maryam Al-Khawaja, a Bahraini political and human rights activist in the Gulf region, works according to specific rules as an activist abroad. She has not returned to Bahrain since 2014.

Her father, Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, was sentenced to life imprisonment when the Bahraini government arrested the leaders of the popular revolution that was crushed in the spring of 2011.

Her father was one of the most prominent human rights defenders in Bahrain, who was brought to trial along with other prominent members of Bahraini civil society and convicted of “organizing and managing a terrorist organization.”

After more than a decade in prison, Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja’s health deteriorated as a result of the torture he was subjected to at the hands of security forces at the time of his arrest and subsequent ill-treatment throughout his detention, including the denial of medical care in recent months.

Despite requests from the Al-Khawaja family to the Bahraini authorities over the years, his medical records have not been handed over to his family.

Maryam Al-Khawaja says her father is now at risk of going blind because he has been denied medical treatment for suspected glaucoma.

As Amnesty International warned last month, “This is the latest display of cruelty by the Bahraini authorities who have a track record of medical neglect of prisoners.”

Due to serious concerns about his health and ill-treatment in Jau Prison in Bahrain, the family of Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja issued urgent calls for his release.

In the interview, Maryam Al-Khawaja explained how the prison administration stopped the medical care and treatments that her father was receiving.

“What we see now is a continuation of this, where the system is trying to make my father submit to what the system wants, and there is a very clear mechanism to send a message to my father that you are being punished now,” she said.

Maryam believes that her father is being punished for protesting against Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s visit to Bahrain in mid-February, when Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja chanted slogans in the prison yard in solidarity with the Palestinians, in addition to his continued insistence on his rights as a Bahraini citizen. He also went on hunger strike last year.

Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja’s suffering in prison is symbolic of how the Bahraini government has dealt with political activists and human rights defenders and the country’s entire population.

In the more than 11 years since protesters took the unprecedented steps of mass mobilization and demanding reform and political rights, Bahrain has become more repressive than it was—and remains a close partner of the United States, the United Kingdom, and other Western countries.

In an interview, Maryam al-Khawaja explained how the prison administration has stopped the medical care and therapy that her father had been receiving. “What we’re seeing right now is this ongoing back and forth, where the regime is trying to get my father to comply with what they want,” she said. “There’s a very, very clear dynamic of sending the message to my father that you’re being punished right now.” She believes that he is being punished for protesting Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s visit to Bahrain in mid-February, when Abdulhadi al-Khawaja chanted slogans in the prison yard in solidarity with Palestinians, along with his continued insistence on his rights as a Bahraini citizen. He went on hunger strike last year.

Abdulhadi al-Khawaja’s suffering in prison is emblematic of the way that the Bahraini government has treated not only political activists and human rights defenders, but the island’s entire population. More than 11 years since protesters took the dramatic and unprecedented steps to mass mobilize, calling for reform and political rights, Bahrain is as repressive as ever—and still a close partner of the United States, the United Kingdom and other Western countries.

One of the things that is interesting about Bahrain and about the revolutions of 2011 generally is that a lot of times, especially in the Western media, they’re regarded as having caused one another—that this revolution happened, and it caused this other revolution. And actually, that’s not quite how it happened. What happened is that each individual country had very real reasons for why they rose up, for why they revolted, for why they took to the streets. A lot of these reasons are similar when it comes to torture, corruption, imprisonment, extrajudicial killings and so on. It is the same with Bahrain. Yes, they were inspired by each other, but they did not cause each other. The Bahrainis were inspired by the Tunisians and by the Egyptians as well, when they saw people take to the streets and the fact that they actually were able to get rid of Ben Ali, and then Mubarak after that.

But the fact of the matter is that the crackdown in Bahrain didn’t start in 2011. It started in August 2010. In 2001, when [then-Emir] Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa said that he was going to bring about a constitutional monarchy, little did we know that he thought what we currently have is a constitutional monarchy, which obviously it is not. He unilaterally changed the constitution to make himself king, and to make Bahrain a kingdom, and then created a parliament that has no legislative or accountability powers, or monitoring powers. So basically, in effect, he set up a system where he became even more of a dictator than his father.

And then, fast forward from there—for 10 years, there was somewhat of a calm. There were still some protests; my father was a part of them. They would still get beaten up, they would still get arrested, but it was generally calm. My father was arrested multiple times in that period. But it wasn’t like it is now. They would get beaten and released; they would get arrested and released. It was more of a revolving door of arrests, as we call them. But something shifted in 2010. Because from 2001 to 2010, whenever people would get arrested, people would blame then-Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman al-Khalifa, the king’s uncle, for being responsible for what was happening. And then the king and the crown prince, Salman bin Hamad al-Khalifa—who were supposed to be better, and who are more liked by the West—would come out and issue pardons.

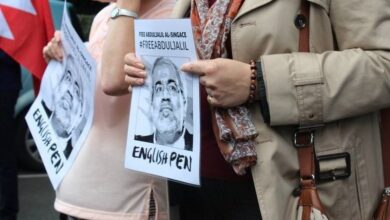

But what happened in 2010 is that there were a number of people coming back to Bahrain who were arrested at the airport, including Abdul Jalil al-Singace, who’s now been on hunger strike for a very long time. Abdul Jalil was coming back from London after having spoken at the House of Lords about torture in Bahrain. Human Rights Watch had also just released a report saying that torture was more widespread and systematic. This was in August 2010. I was one of the people who had to leave very quickly from the country because I was under threat of being arrested as well, and I left to London at the time. I remember during that period, from August until December 2010, it was during Ramadan that these crackdowns happened. People were saying, “Well, you know, it’s going be Eid. The king and the crown prince are going to come out, they’re going to release everyone. And it’ll be like it always was.” But something shifted that year. And instead of coming out to release people, the king and the crown prince came out to support the crackdown. And that’s when we realized that something had changed. Something had shifted in the environment in the country.

And in that period, from August 2010 until the uprising started in February 2011, torture came back. We also saw the number of cases of children who were being kidnapped. Some of them were stripped naked and had their pictures taken, and then they were threatened that if they did not work as informants for the police, their pictures would be released on the internet. That was new in 2010; we hadn’t seen that before. My job was mainly documenting these cases, and then using them for advocacy abroad.

So when February came along, and when Tunisia and Egypt happened, people were already angry. In Bahrain, we already had a situation that was very ripe for an uprising. And when people came out, they wanted to believe that things could be better, just like they did in 2001. When the king made all these promises, people wanted to believe that things would get better. When people came out on the streets, they weren’t even calling for the fall of the regime. They were saying: Follow through on your promises from 2001. Give us the constitution you promised. And so that we can move forward with the situation, release the political prisoners, stop the torture, stop going after the children, and so on. It was only after they started killing people on the streets that people said, well, you know what, we asked for a constitution that represents the people, but you’re shooting us for it, and therefore, the regime has to go.

And that’s when the shift happened. I remember where I was there in that moment, as I walked out of the hospital [in Manama] with the doctor after the first person was killed by police. There were these massive crowds standing outside the hospital. And as soon as the doctor announced that we had the first killing of the uprising of Bahrain, people started chanting, “Al-sha’ab yurid isqat al-nizam!” That’s when it started. It was after the murder of the first person who was shot in the back while running away—so not even confronting police.

And from then on, the numbers increased. The numbers kept increasing and increasing and increasing, and suddenly you had tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people on the streets protesting. And, interestingly enough, because Bahrain is a small country, it didn’t get as much attention in regards to the numbers, because they seemed quite small. But actually, if you look at it per capita, Bahrain had some of the largest protests of the revolutions of the region, because we had almost 40 to 50 percent of the population on the streets.

This is also because Bahrain, in my opinion, has a very old civil rights movement—one of the oldest civil rights movements in the region. Our civil rights movement started in the 1920s. People were protesting, and if you look at videos from the BBC, from the 1940s or 1950s, they do interviews with leaders of the movement then, who talk about the exact same demands that we talk about today. They talk about the constitution; they talk about not delivering on promises. You see that there’s a correlation between the uprisings that have happened almost every 10 years since the 1920s, until now.

We saw this percentage of people coming to the streets that we’ve never seen before. And people were like, “You know what? I can now say whatever I want.” You had all these banners going up. And you had some politicians trying to tone it down, saying, “Don’t say, ‘Isqat al-nizam.’ Sit down with the regime, talk about reform.” People are like, “No, if they’re killing us in the streets, we’re going to say the regime has to go.” And of course, then the first crackdown came, on the 17th of February 2011. I was in the Pearl Roundabout when that attack happened. It was in the middle of the night, people were sleeping, and they attacked us without warning. Several people were killed that day. I don’t remember it as well, right now, because you know, with PTSD, you tend to block a lot out. But I remember the telling of the story of what I know happened.

Just remembering the way that they were shooting, knowing that there were men, women and children in that square, but they were shooting nonetheless, with no regard for who they were hitting. How narrowly some of us were able to escape from the square that morning. That’s when the military came in as well—a military that is a “major non-NATO ally,” a military that gets trained in the United Kingdom and the United States. The fact that the Bahraini regime decided to use the military, in that instance, against protesters who are unarmed and peaceful, was, again, a form of messaging to us as protesters that they didn’t think that they would be held accountable. Because they know that using the military that has been trained in the West would have consequences. But because they’re an ally, because they’re in the Gulf, it’s different, of course.

I left the country shortly after that first attack. And then the Gulf Cooperation Council sent their army into Bahrain—the Peninsula Shield, as they called it, mainly from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. They attacked the square, killing people and burning everything. There are horrific images that came out of that day of people being shot in the head, execution-style. Since then, the government has done what they do best: They used a lot of violence to crack down on the protesters, and then—what I believe to be through the advice of their Western allies—learned how to use the judiciary as their main source of oppression.

The Bahraini government has been using the sectarian card for a very long time now, like the Saudi government and others in the Arab world. They use it to drive a wedge between communities, to make them less politicized in a sense, but also to make mobilization harder for people, to make the protests and the chants not about human rights and dignity, but about certain sects. When the GCC deployed the Peninsula Shield Force into Bahrain in 2011, they didn’t say it was to crush the revolution, they said it was to “protect” Bahrain from “foreign interference.” There are many people, including in the Gulf, who supported protests in many countries in the Arab world, but stopped at Bahrain, because the Bahraini government and the Saudi government played that sectarian card, using Iran as a scarecrow, to drive them away from lending support.

There was an issue with solidarity in the region and how far it went—what people were willing to stand in solidarity with and for, versus not. And that’s something that even we, as Gulf activists, tried to break through. For me, as a Bahraini, I believed and supported the Syrian revolution because of my ethics and principles, and I believe in the fight for people to have their freedom and to have control over their own country and self-determination. And as well as that, I also felt that it was important for me to be very vocal about it. Because as a Bahraini Shia woman who was an activist, I knew that for me to stand in solidarity with the Syrian revolution, it makes a difference. And I wasn’t the only one. There were Syrian activists who did that, Palestinian activists, Egyptian activists. There was a group of us who were trying to break through those stereotypes and those discourses that these governments were creating to pull us apart.

Maryam al-Khawaja at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy, in 2017. Photo courtesy of Maryam al-Khawaja.

And this is something that we see over and over again. These governments try to create these narratives, to make sure that we can’t work with each other. Because at the end of the day, one of the biggest threats to these regimes is when we learn to work together, when we learn from each other, when we learn what the wins and losses are and how to come about them, what works and what doesn’t, and when we actually stand in solidarity with each other. It does make a difference. And so of course, what they’re doing is trying to figure out, well, how do we split up these civil society groups? How do we split up these activists and protesters from each other? And they tried to do it through the use of sectarianism, obviously, because that’s an easy one to play on. There was a joke that I liked, which was—the Bahraini government has accused me of being an Iranian agent, they’ve accused me of being CIA, they’ve accused me of being Mossad. And I always say that I must be extremely smart, if I’m the only one who can bring those three to agree on something, right?

That’s one thing, just how ridiculous their claims are. And then the other part of it is, it’s never really about sectarianism, if you look at the situation in the country. Look at Iran, which is supposed to be the leading country in protecting Shia rights. But if you look closely into their prisons, the majority of the prisoners of conscience are Shia. They’re the people who are being persecuted and oppressed. Saudi Arabia is the same thing. There’s a huge number of Sunnis who are also in prison and tortured in Saudi Arabia. These countries claim to be standing for something because it serves a purpose—politically, economically or whatever it is. But when you look at the details of who they’re persecuting, who they’re going after, it’s always the people who actually stand against sectarianism.

How effective can you be as an activist outside the country, and what are your expectations? What do you think human rights organizations should do to highlight the Bahraini situation, such as prominent human rights defenders in jail like your father?

It’s interesting, because I actually wrote a paper for the Brown Journal of World Affairs on what we’ve learned since 2011, outlining 10 lessons from the past 10 years. There are some rules that I’ve lived by in the past 10 years that have served me well. One is that, when I left Bahrain, I immediately made a rule for myself that I do not have the right to ask people to do something that I cannot do myself. So, I would never give myself the right to be sitting in Copenhagen or wherever I am and to tell people in Bahrain: You need to go out on the streets, you need to protest, you need to put your life at risk. Because unless I’m able to be there on the ground with them doing those protests, then it’s not OK for me to be sitting in the comfort of where I am and to ask people to put themselves at risk. I can report on it, I can say that these protests are happening or have been organized. But I can’t tell people or ask them to do those things unless I’m doing it with them.

The second rule was that, since I’m not on the ground, when I’m talking about Bahrain, or when I’m talking about other countries, I’m a loudspeaker, not the spokesperson. My job is to relay what’s happening from what I know from people on the ground. I went back to Bahrain in 2014 and spent some time in prison, and when I came out, I tried to go around and meet with people. And I realized that no matter how much contact you have with the situation on the ground, there are always some nuances that are going to be lost when you’re not actually there. So it’s very important that we hold that humility for ourselves.

We have limited energy and limited resources. We need to be extremely strategic in how we use these limited resources that we have, whether it’s people or tools or partners. That’s why I wrote the paper about the lessons learned from the past 10 years—that was my form of self-reflection. Now I’m trying to come up with a strategy for myself. I can’t speak on behalf of other people, obviously. But now I’m trying for me, with myself. How do I come up with a strategy that I think best serves this cause or the causes that we fight for?